Design Thinking

Using Design Thinking to Address Community Issues

In the following I summarize the design process I ran in collaboration with the personal science community in order to develop a peer production solution for them.

While doing this, my aim is primarily to share the user research and design methods and tools I used, so that others may find guidance on how to co-develop solutions addressing community issues.

Motivation and starting point

After more than a decade of existence, the personal science community has observed that “the community does not scale up” and that “everyone tends to start their projects from scratch”. This indicates that despite having an active community of self-researchers who run and share their own projects, individuals encounter difficulties accessing the knowledge hidden within the community. Information is often disseminated through word of mouth. The community places a high value on sharing methods, data, and lessons and regards its members as equal peers, aligning with the principles of peer production. Consequently, they were interested in trying such an approach.

Methodology: Design Thinking

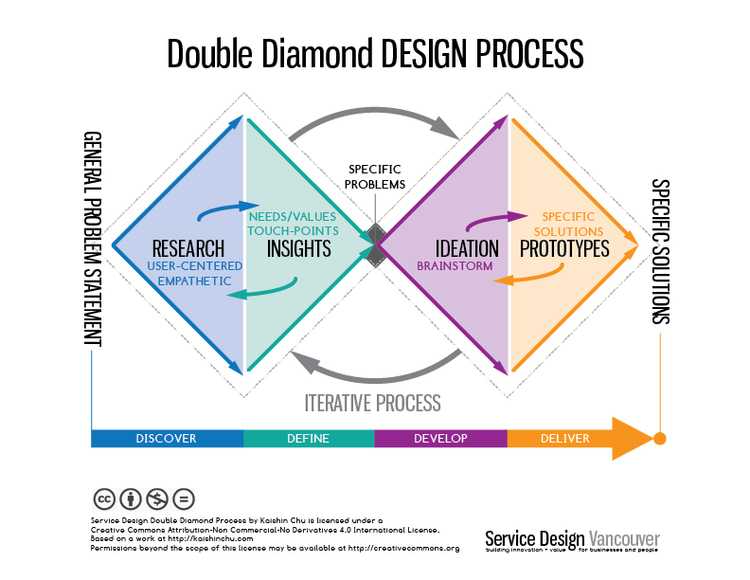

To address this loosely-defined task, I employed the design thinking methodology, which is described as a “human-centered approach to discovering innovative solutions to complex problems” (Taheri et al., 2016). The specific framework I utilized is known as the “double diamond”. As illustrated in Figure 1, this framework leads from a broad problem statement (on the left) through the exploration of two “diamonds” that aid in gaining a deeper understanding of and prioritizing the problems, as well as in prototyping and testing solutions, ultimately leading to specific solutions. Emphasis is placed on frequent and close collaboration with end-users and other stakeholders to develop solutions that truly address their needs.

Stakeholder analysis

Initially, I sought to identify the primary stakeholders for this task, specifically those individuals who would be affected and interested in collaborating to address the issue. In the context of personal science, this encompasses a loosely defined community of individuals who employ research methods to explore their personal questions and concerns. Many individuals engage in personal science independently, without any formal community ties. However, there are certain communities, such as Quantified Self and Open Humans, where participants exchange ideas and insights online through platforms like forums, Slack, and virtual meetings, with occasional in-person events for sharing experiences. Notably, my research lab maintains a close association with Open Humans, with both my supervisor and another lab member serving as community managers. Additionally, there are connections with community managers from Quantified Self, establishing a solid starting point for our efforts.

As our first step, we created personas (archetypical community member) based on the experiences of my lab colleagues and conducted interviews with community members, as part of prior research. This approach allowed us to gain insights into the motivations and challenges faced by various community member and end-user groups, enabling us to prioritize specific aspects.

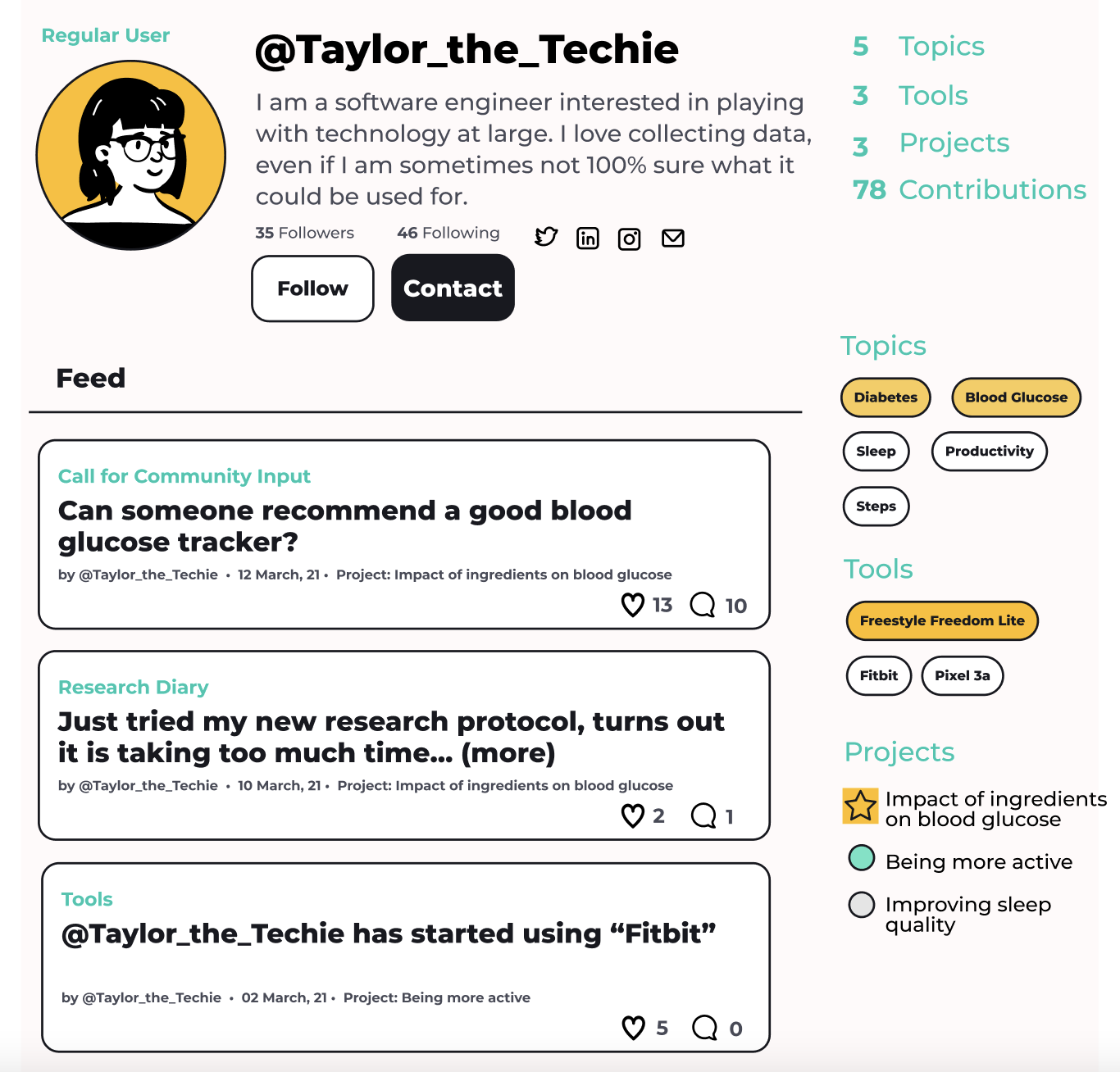

Here’s an exemplary persona:

| 1 | Taylor the Techie |

|---|---|

|

“What can I do?” Taylor is a software engineer who is interested in playing with technology at large, including playing around with hardware. Taylor loves collecting data, even if they are not 100% sure what it could be used for. |

| Motivation | Internally motivated, excited about technology, likes to spend time on it in their freetime |

| Challenges | Finding a purpose to apply their skills and interests |

| Community | Self-research chats, likes to help people with their technology- and data-related questions |

| Skills | Meta research: beginner Data analysis: intermediate Coding: expert |

Click here to see all personas

Identification and prioritization of problems

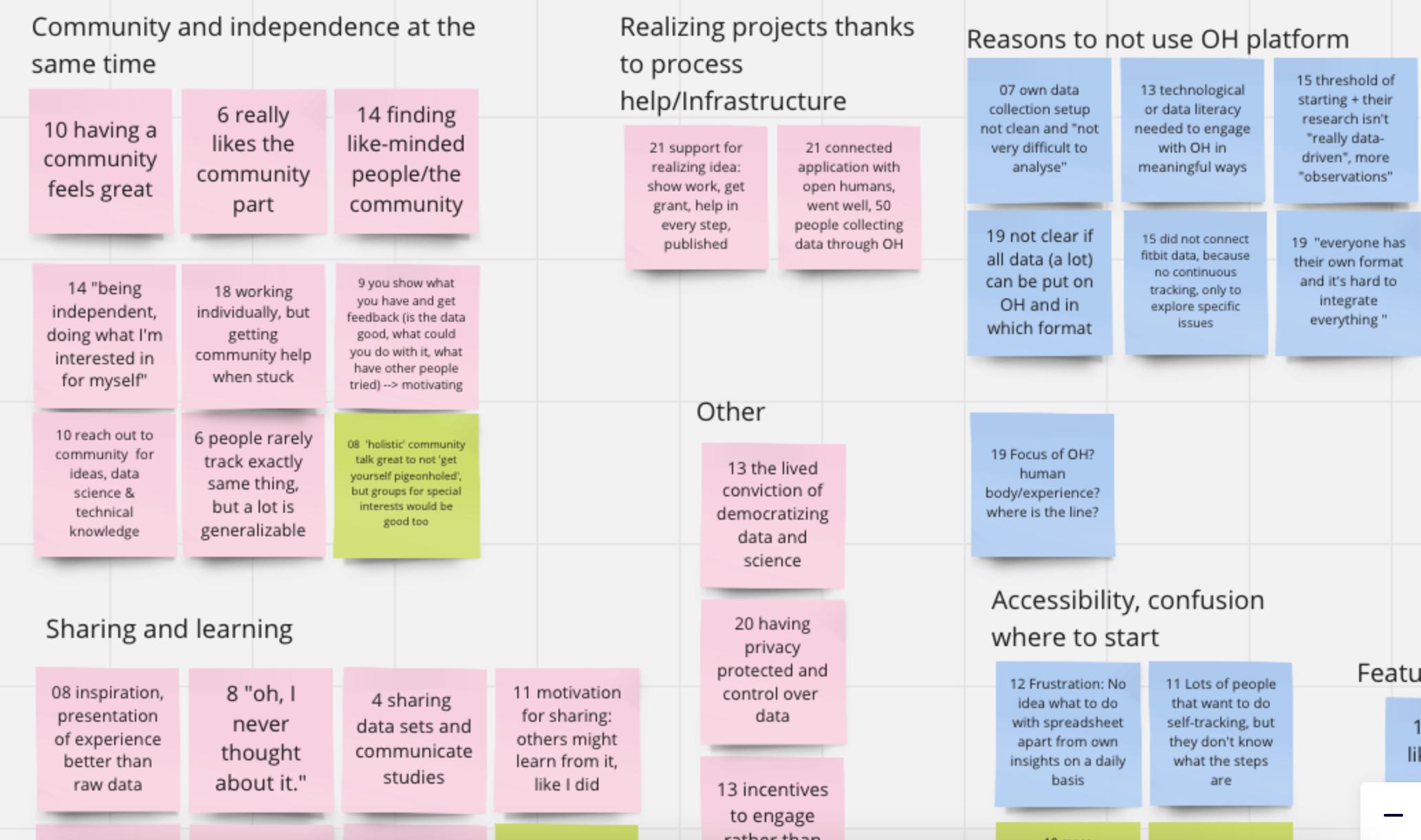

Next, I tried to get a better understanding of existing problems. I was new to the community at that time, and brainstormed all resources and stakeholders that were accessible to me and could give me a good overview in a reasonable amount of time. In my case, I relied on two steps: some members of my research lab had shortly before led interviews with people doing self-research (representing the larger community). The interview’s focus was on motivations for the practice, but they also contained information about issues, ideas and wishes. From these interviews, I extracted and copied relevant information on virtual post its (using Miro). Using the “Rose-Bud-Thorn” method, I categorized all of the post its into roses (motivations/positive points), buds (ideas/wishes), and thorns (issues/pain points), and clustered them in different topic areas (see Figure 2).

In the second step, I discussed the issues on this board with team members, who are also community managers in the personal science community. Learning from their experience (for example, about ideas that had already been tried, but did not work), helped me to prioritize some issues, motivations and ideas. The prioritized points were “Something that encourages people to share their progress”, “A way to find what has been done / the knowledge that already exists in the community in an unstructured way” in form of “some sort of cross-referenced information system”, “Forming long-term social motivations”, and “Analysis assistance”.

Ideation and prototyping

In the next phase, I started brainstorming potential solutions. This included mainly the development of wireframes for an online social platform where people could share their projects and interests, discuss and connect (see Figure 3).

I discussed this idea in detail with a community manager/team member. Several points of criticism arose, particularly regarding the feasibility of developing a custom platform within the context of a PhD (as we aimed for a quick launch and live testing). Another concern was the reliance on gaining adoption from a significant number of users, especially if each user could only post their own projects. Similarly, the effectiveness of question items was questioned, as outreach and obtaining quick answers might be easier on larger platforms like Reddit. Despite these hesitations, the major categories (user pages, projects, tools, topics) were deemed suitable, representative of relevant community knowledge, and a potential foundation for addressing the issue of creating a cross-referenced information system.

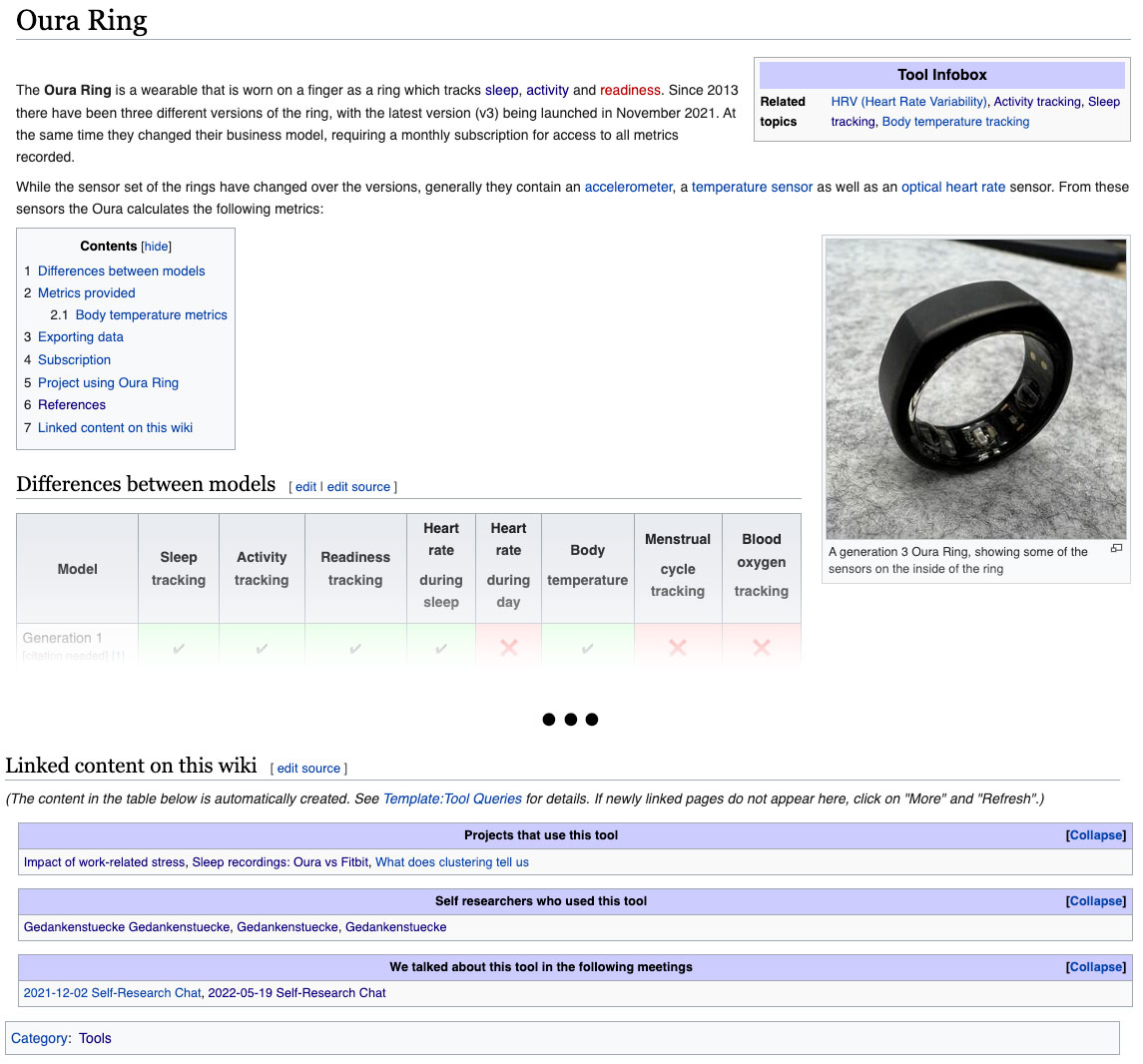

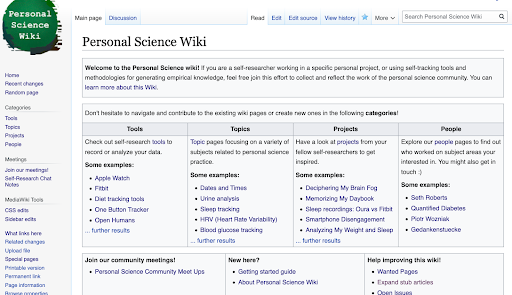

Personal Science Wiki

In the following, I endeavored to find a solution while preserving the core concepts of the previous platform prototype but with a more easily deployable infrastructure. This gave rise to the concept of the Personal Science Wiki (for more information about the wiki concept, please see Chapter 3 of my thesis). By utilizing MediaWiki software, we could swiftly establish a peer-production environment for community knowledge management, enabling us to focus on structure, content, and genuine user feedback. Before initiating development, we consulted with a community manager from a different personal science community to gain his perspective. Following his positive feedback, we proceeded to implement the initial version of the wiki and presented it during a community meeting to gather impressions and feedback. See Figure 4 for an early screenshot of a “Tool” page.

Live testing and improval

The wiki was usable from that moment, and some community members started using it. To create seed content, we imported over 370 talks about self-research projects from the archives of Quantified Self. In order to collect user feedback and improve the wiki, I set up several pathways: Dedicated pages on the wiki itself, a slack channel, and some dedicated minutes in weekly community meetings. This early test phase helped us remove some technical issues, add content (imported and user-generated).

User study

In the following, we ran a more formal user study, in order to explicitly test the usability of the platform and primary user flows, and to get feedback from people that were not (yet) wiki users, and/or new to personal science. Once the ethics review of by the institutional review board was positive (this process usually needs to be done if you run an academic study with participants), I recruited 21 people to participate. This study consisted in an online usability test (meaning, study participants did tasks on the website (mainly looking for information), while sharing their screen with us and commenting their experience), as well as a card sorting study (details here!) to learn more about how information on the wiki should ideally be structured.

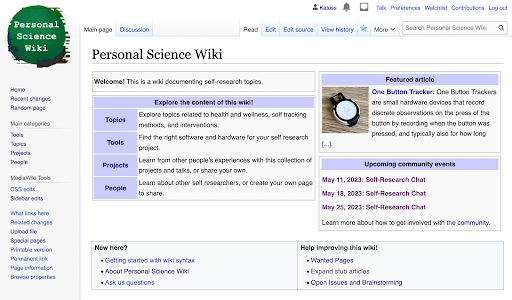

The usability test provided valuable insights. For instance, it allowed us to enhance the homepage (from Figure 5 to Figure 6) and to restructure page templates for improved user-friendliness in locating relevant information. Additionally, we gained valuable insights into the kind of information users anticipate finding in such a resource and their preferred formatting.

You can find more details on the usability study in Chapter 4 of my thesis.

Impact

I devoted considerable thought to determining how to measure the effectiveness of the wiki and its ability to address issues. Measuring success was not straightforward, as many conventional Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) were not applicable. Additionally, metrics like the number of users and posts were challenging to gauge during the early experimental phases of system development. Nevertheless, some indicators were discernible. The wiki was actively utilized by a small user base, with some users contributing regularly, resulting in thousands of edits. Furthermore, the wiki served as a platform for sharing information within the community. From September 2021 to May 2023, wiki links were shared in 56 ‘self-research chat’ community meetings.

Moreover, our engagement with the community provided us with a deeper understanding of personal science issues and potential solutions, as well as insights into how our values aligned with peer production approaches. The usability study not only identified specific usability issues with the platform but also shed light on user expectations for a personal science knowledge resource. The card sorting study revealed new insights into how individuals organize information related to self-research.

In its current state, the wiki serves as community knowledge management infrastructure in use, but facing challenges e.g. due to limitations in the MediaWiki software. The lessons learned, as detailed in chapters 3-6 of the thesis and in the ‘further reading’ section below, provide a foundation and guidance for future developments in self-research knowledge management.